This article was originally published on World Economic Forum. Republished in accordance with Terms of Use.

by Samir Saran and Mihir Sharma

Since the First Industrial Revolution, growth and welfare have depended upon increasing the efficiency of production. Specialization, manufacturing, electricity and the computer all increased productivity, GDP – and thereby wages and national welfare. Higher wages did not just spur consumption of more goods and services, but also meant bigger national budgets through tax collection. A virtuous circle of prosperity was created. Some gained more than others, creating persistent inter-generational inequality; but, in absolute terms, economic means were enhanced across all major population segments. (Except, of course, for those places that were colonized and subject to deliberate exclusion from such gains.)

This relationship – between productive efficiency and economic growth and wages – is now breaking down in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Digital technology is creating digital societies; mass services are replacing mass manufacturing as the source of welfare enhancement; and shared assets are supplanting exclusive asset ownership.

Providing the same final utility to a consumer requires the production of fewer manufactured goods. The sharing economy, meanwhile, means previously under-utilized assets are being more productive. When India’s economy hits $5 trillion (perhaps five-to-seven years from now), it will at most have about 50 cars per 1,000 private individuals (it is 22 cars today). Japan, which is a $5 trillion economy today, has close to 600 cars for 1,000 people. McKinsey has forecast that India will overtake Japan in total car demand in 2021. But this figure does not reveal demand for new vehicles in per capita terms. In spite of the large gap in private car ownership, private ride sharing and other mobility service options will narrow the transport experience between the residents of Japan and India.

Divergence in the automotive sector is particularly telling. In the 20th century, mass assembly-line production created efficient producers with consequently higher incomes – a feature of what came to be called “Fordism”. In the 21st century, individuals and economies are reaping welfare gains from being more efficient consumers. Consumption efficiency is replacing production efficiency – a trend we can call “Uberism”.

The changes accompanying this shift from “Fordism” to “Uberism” are difficult to see in economic metrics. The more efficient use of assets, the shift from traditional manufacturing to innovative mass services, or the provision of greater utility through fewer goods and less physical activity, may appear on the national accounts as value destruction or stagnation rather than as GDP growth. Yet welfare gains in the future are likely to do just that: appear, when observed through the economic frameworks of the past, like slower and lower growth.

This implies that three major trends need to be theorized and engaged with by economists and political scientists:

First, a replacement is needed for GDP (as we define it now) as a measure for economic progress. Governments and policy-makers chasing GDP growth in an age where welfare enhancement may not be reflected in GDP will not be serving their citizens well. Their policy emphasis will be on objectives that are irrelevant to the 4IR. Barring a few sectors (food production is remarkably resilient to the shared economy, but certainly subject to efficiency gains) and finished goods (personal communications devices being one of the exceptions), a consumption basket biased towards the drivers of production-led growth is now an incorrect marker for proper economic assessments.

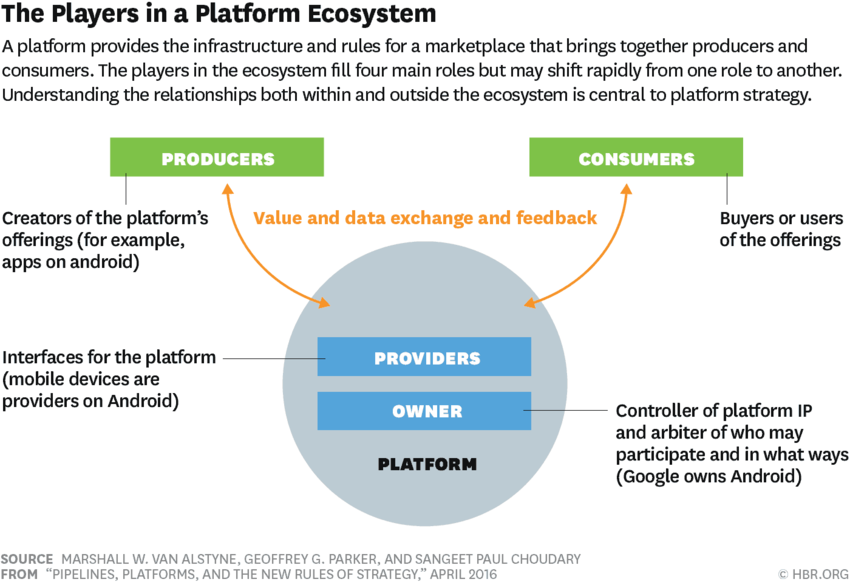

Second, a new theory of productivity, labor and consumption is needed. Earlier economic strength came from creating per-unit value; but increasingly what matters is overall valuation. The strength of corporations or enterprises is already being negotiated in these newer terms, but national balance sheets continue to plod along old paths. Compare, for example, ExxonMobil and Apple. In 2007, boosted by then-unprecedented increases in the price of oil, ExxonMobil first breached a market valuation of $500 billion. That year, its revenue was $400 billion. In other words, the revenue generated by Exxon at those levels was much higher than the revenue of Apple at a $1 trillion market capitalization. But investors believe in the future of platforms, and have come to a consensus about the importance of placing value on factors external to a network itself. Platform economies are validated by the number of persons on the platform and not through plain vanilla per-unit production and sales processes of the past. The intrinsic value attached to the on-boarding of an individual or a billion of them onto a platform, or more broadly a “service ecosystem” (say a Facebook, Google or even Aadhaar) is captured by stock markets, but not by GDP assessments.

An inevitable consequence of this process will be a re-evaluation of the economic and political feasibility of current intellectual property rights (IPR) regimes. Today “onboarding” (getting users to sign on to platforms, services, operating software etc.) prevails over “gatekeeping” (charging IPR fees for use/user access). So are today’s IPRs useful when it comes to creating value for countries and citizens in Industry 4.0? This means the nature, definition and pricing of “innovation” itself might have to change: the happenings around Android and iOS are already offering some pointers to the future.

Finally, this discussion would be incomplete without delving briefly into the need for a new theory of social organization. Political and social arrangements that revolve around citizens’ identities as workers are unfit for today’s digital societies of today. The reconfiguration of the workplace (from factory floor to handheld device, for example) and of the nature of work itself, as discussed earlier implies deep changes to political structures and social support networks. Can trade unions stay relevant in this new era? What is the relevance today of party politics that developed out of First Industrial Revolution class conflict, deriving their raison d’etre from the working classes on the one hand and business owners on the other?

The reconfiguring of the primary identity of the citizen as consumer and as asset owner is at the root of all challenges to the old, class-based political order. Intangibles – people’s time, their whims, their platforms and their engagements on social networks – are more important and are changing politics already. The data economy will complicate the importance of passport-bearing physical beings (until very recently, comprehensive national power placed a significant emphasis on population count) since it recognises only “users” and their interactions with service ecosystems. Users don’t reside within territories and nor will their political and economic choices. Citizenship on a mobile phone is already changing individuals’ expectations from – and commitment to – prevailing nation states, with major and understudied implications for both state legitimacy and agency going forward.

The three-century reign of the manufacturing nation may now be over. Welcome to the age of the platform nations – templates for which are yet to be discovered.

| Technology, AI and ethics.

| Technology, AI and ethics.